‘Zero Dark Thirty’ tells the story of how American intelligence operatives tracked down Osama Bin Laden hiding in Abbottabad, Pakistan, in 2011. Or does it? As it deals with the shadowy world of intelligence, we will never quite know unless the official documents are made public (which in Britain happens thirty years after the fact, as per the ‘Thirty Years Rule’). The film is from director Kathryn Bigelow (the first female winner of the best director Oscar for 2008’s ‘The Hurt Locker’) and writer Mark Boal. Originally, the pair had been working on a project surrounding the Battle of Tora Bora in Afghanistan in 2001, which had been a previous military attempt to capture Bin Laden, but when they heard the news of the Abbottabad raid they decided to shelve that project but still use their intelligence contacts and information to form the basis of ‘Zero Dark Thirty’, perhaps sensing they had a foot in the door advantage over anyone else thinking to do the inevitable and dramatise the event on film.

The exact nature of the real intelligence they had access to, and its accuracy, is still a very hot topic of debate in America, with the filmmakers to undergo yet more investigations by the government as confirmed this month and with the Republicans during the last presidential campaign claiming that they breached security protocols and put the intelligence services at risk. Even more contentious is the film’s depiction of the use of torture on suspected terrorist prisoners and the fact that it could be argued that real necessary intel was garnered this way, and indeed whether or not the movie actually promotes torture.

However, this misses the real question. Is it accurate? If the torture and what came from it is entirely true to actual events, then the filmmakers have done their job. If those events are knowingly fictionalised and yet are presented to us as fact, then they have some very serious questions to answer. This is the only point that really matters, but to touch on the debate very slightly, despite the fact some information does get obtained from torture which eventually leads to closing in on the target, it takes the better part of a decade to do so, it’s not exactly displayed as the most effective or efficient method of gathering information by the film, all moral questions aside.

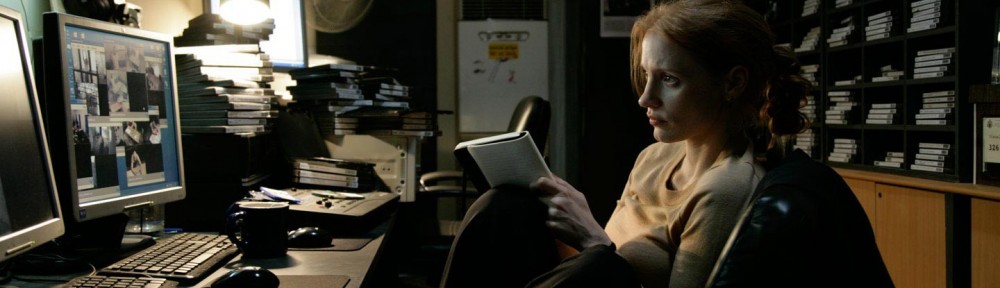

The film walks, successfully, a curious line – keeping us both emotionally distant but involved in the beginning, and slowly reeling us in until cold barrenness finally gives way with the emotion of the main character in the final scene, and quite emotively so after almost three hours of harsh reality. It doesn’t take much more than a simple nod in the right direction for us to invest throughout, as the subject matter is so familiar to everyone. We largely see events through the perspective of female CIA agent Maya, played by Jessica Chastain, a fictional agent but one reportedly based on a real person. Up for an Oscar for the role, she convinces throughout, as do all the supports, though the one scene when the film very consciously tries to ramp up the tension was way too obvious and could have been done much more effectively.

For some real pathos, the cinema I watched this in made a special effort, which was good to see, for a severely disabled man, requiring a machine to breathe, to watch the screening. It was impossible not to consider that he himself may have been involved in the conflict. Provided this is an accurate depiction of real events, it becomes an extremely important film to see as it is an effective and debate provoking reminder of both the capacity for bloodshed in the world, and the difficulties of modern civilisations trying to keep that bloodshed at bay without unduly causing more. Timely with Britain’s announcement over the last couple of days that she is to send troops into Mali: is it part of a larger sensible strategy, or an ego and hopeful ratings boost for one of the most unpopular Prime Ministers the country has ever had (perhaps just as Margaret Thatcher’s public appeal soared with the tides of war {who’s son ran an arms company incidentally})?

Zero dark thirty refers to the military term for half past midnight, and, although I don’t think it’s mentioned in the film, the Abbottabad operation was code-named Operation Neptune Spear, for those of you who like to know mission names. For another film, one which largely flew under the radar, that deals with similar themes of torture and national security see ‘Unthinkable’ (2010) with Samuel L. Jackson and Michael Sheen.