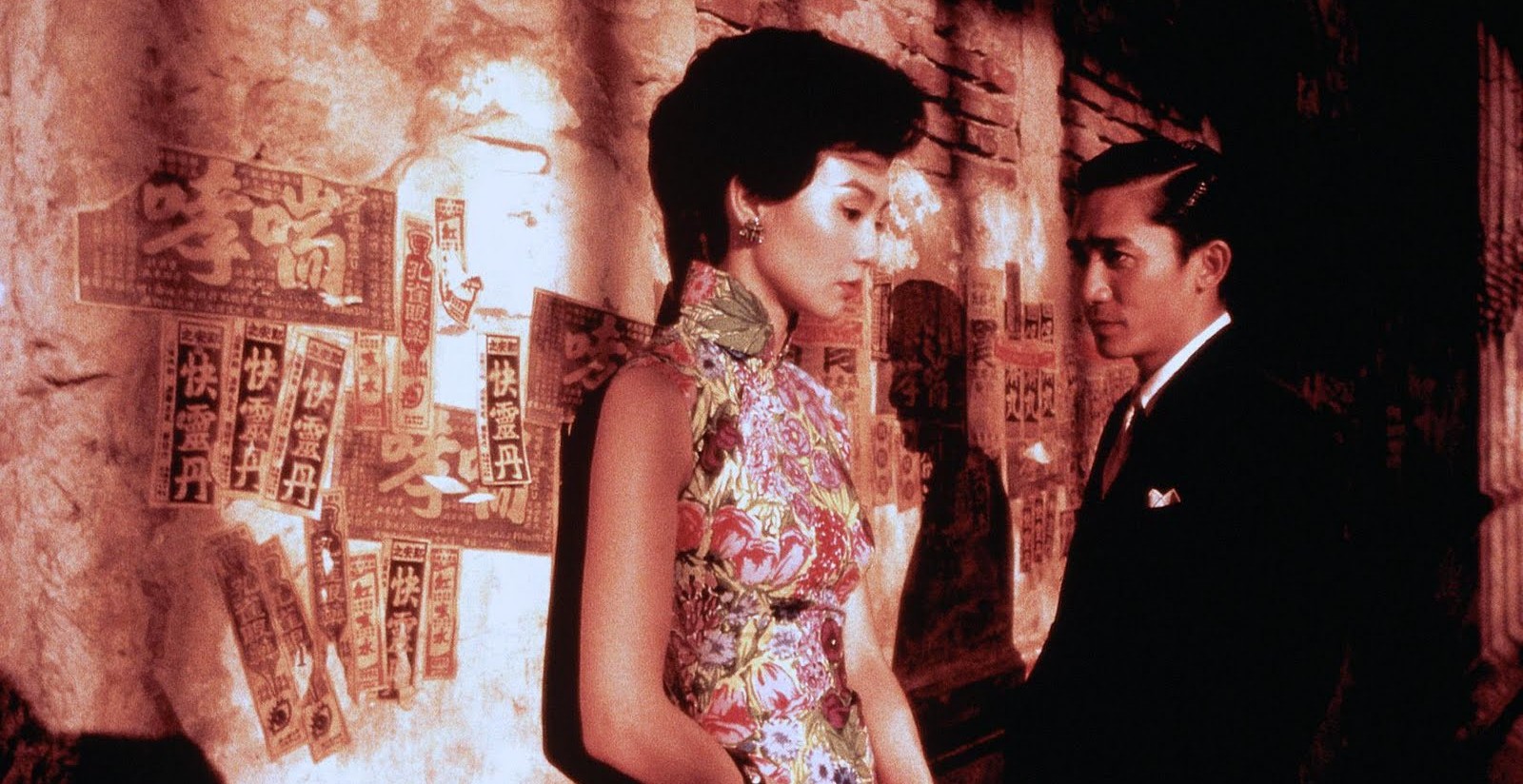

The constant linking motif throughout this film is the slender, beautiful and delicate figure of Maggie Cheung, accentuated by a menagerie of elegant dresses that relentlessly hug her frame, constraints of time and place, perpetuating an almost haunting, nostalgic image of perfection with the way the film has been shot, and its poetic reflection of love. On several occasions, once very near the beginning, director Kar Wai Wong uses to great effect brief images of simply Cheong’s hand and arm on a doorframe and then later a banister to powerfully convey sensuality and sexuality respectively. Throughout the film the same score of moody string laden music plays, mixed with the sonorous baritone of Nat King Cole singing in Spanish which, together with the elegance of the leads and their costumes, creates the atmosphere of a tango being danced throughout the narrative, with all its dark heady promise verging on catastrophic despair.

Cheong plays the wife of a husband who is having an affair with the married woman next door in 1960’s Hong Kong. Circumstances bring her closer to that woman’s husband, played by Tony Leung, and the two find solace in each other’s company as they ask each other how their partner’s infidelity could have come to pass. A crutch for one another, they are in many ways isolated in their own company, unable to share their turmoil with anyone else and yet unable to admit they are falling for each other, hoping to resolve their marital difficulties eventually but also unwilling to consider themselves in the same category as their other halves, that perhaps the simple act of their partners spending time together whilst they were at work was enough for their existing love to shatter.

The film has an almost voyeuristic feel to it – the camera is often at a distance from where the actors are talking, and at times it is allowed to remain stationary whilst the characters move past it to continue conversing somewhere out of shot. It kind of fits with the increased secrecy of their meetings, but the time frame is also very cleverly, and subtly, used to great effect here, both in a localised and a general way, and with the inclusion of the iconic and ancient setting of Angkor Wat and the film ending, as it begins, with a line of poetry that uses the imagery of looking through glass, the style of the piece is finally, and triumphantly, consummated.

It’s achingly beautiful in many ways and wonderfully acted, and it will involve you in the onscreen romance, but it just might break your heart a little in the process too.