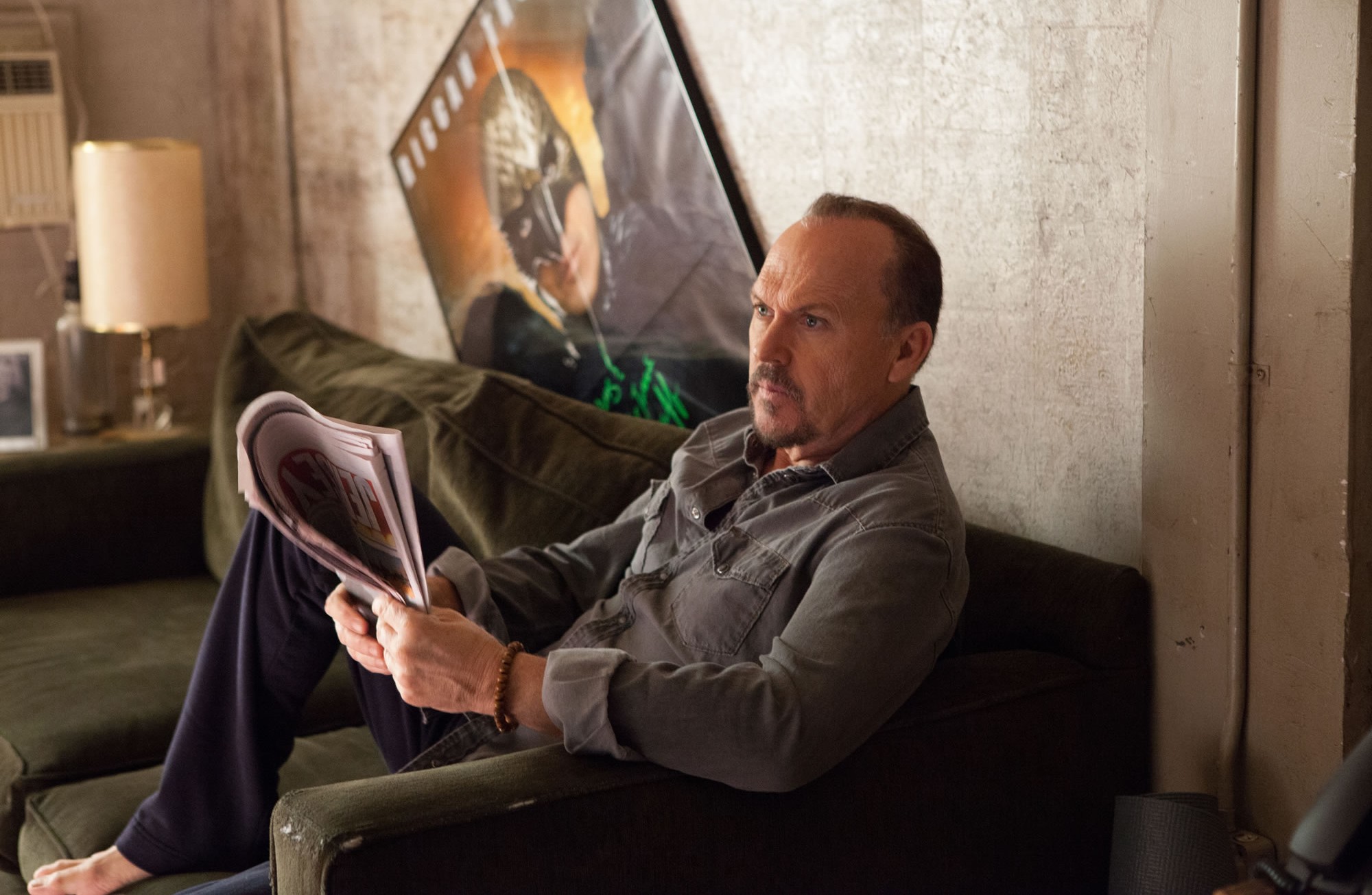

Hot favourite to take home the Oscar for best picture and best actor this year, ‘Birdman’ tells the story of Michael Keaton’s Riggan Thomson who is attempting to put on his first Broadway play: an adaptation of Raymond Carver’s short story ‘What We Talk About When We Talk About Love’ starring, and written by, himself. There is a knowing element of self reference – Riggan is most famous for a series of big-screen hits surrounding the fictional superhero ‘Birdman’, but when he refused to do the fourth instalment his career went on the back burner and then dropped off the radar completely, we are told Birdman 3 came out in 92 which is of course when ‘Batman Returns’ was released and it is fair to say Keaton never really hit the spotlight again afterward until now, although he has had some really good supporting roles recently, in ‘RoboCop‘ and ‘Need for Speed‘ for example.

The story thus allows for a lot of commentary regarding the movie industry as a whole, blockbuster success vs real art, movie stars vs stage and ‘serious’ actors etc. and both particular to the performing arts and also transcending them is the central concept of the need to feel valued, and what damage a fruitless search for validation can do as well as the precipitous dangers of ego. It’s directed by Alejandro González Iñárritu (‘Biutiful’ 10, ‘Babel’ 06, ’21 Grams’ 03, ‘Amores Perros’ 2000) and what makes the film primarily stand out is his decision to film the vast majority of the movie in what is displayed as one continuous take – all bookended by a sort of prologue and epilogue, with the take itself interjected by two time-lapses and one fade to and from white (with the occasional bit of digital manipulation to merge locations and so on).

It’s not the first time this has been attempted in a feature film – Hitchcock’s ‘Rope’ (48) is the most famous example, and the scene with Michael Fassbender and Liam Cunningham in ‘Hunger’ (08) also springs to mind, but there Hitchcock was hindered by technology: using actual film limited the length of his takes, in the digital era a film in one shot is entirely possible. You do think to yourself ‘well, so what?’ after all, stage performers do continuous takes sometimes twice a day every day for months. As if sensing the obvious attack on his otherwise superlative work, Iñárritu flits continuously and seamlessly between backstage, outdoor and rooftop scenes and those taking place onstage in front of a live audience, beginning with the previews and then the opening night performance. Together with the logistics of filming the thing it is all very impressive – in fact the camera operators in particular deserve a lot of credit. There’s a knowing nod to another classic of cinema as well – ‘The Passenger‘ (as if to lovingly stamp his knowledge of film into the work), where at the end the camera famously travels from an interior shot seemingly straight through a barred window to the outside. To film it a rig was built so that the bars slid apart as the camera moved forwards, and here after one of the time-lapses the camera similarly passes with ease through a barred window – at first I thought perhaps that it was just a zoom and a change, or that there are no bars and it’s simply digital, but I think maybe you can actually hear the sliding of metal if you listen carefully …

On first viewing it was all a little distracting (I had no idea long takes were involved), rather like watching a friend perform you are slightly nervous for everyone and it is relentless, leaving The Red Dragon with a question as to, despite its technical wizardry and craftsmanship, does it really work as a piece of entertainment? On second viewing though, it was a lot easier to relax and appreciate what is on display, and it is pretty marvellous – but it wouldn’t mean half as much without a tremendous and almost faultless central performance from Keaton, whose perhaps biggest achievement is that he always seems utterly in control of what’s he’s doing, despite the onerous weight placed on his shoulders. We watch Riggan run through the gamut of human emotion as he contends with the stress of the venture, the egos of his troupe, his own feelings of low self worth, the distance he’s created between him and his family, and the constant pecking of his alter ego ‘Birdman’ who has been chipping away dangerously at his psyche for decades and whom we see depicted onscreen as well, sometimes literally hovering over his shoulder.

It’s not completely perfect, there are some hiccups like when Naomi Watts and Andrea Riseborough move in for a lesbian kiss (the lead up to this is probably the weakest part of the film) and where there had been silence, drumbeats kick in – but too early, all but ruining the palpable tension the moment had created, and whilst there appear to be some fluffed lines there equally seems to be great improvisation – in particular from Riseborough who is about to walk in front of the audience when one of the stage hands gets in the way, and she immediately turns back to Keaton to deliver a line instead of just freezing awkwardly, before heading back to the stage. Also in support are Zach Galifianakis, Emma Stone (as Riggan’s daughter), Lindsay Duncan, Amy Ryan and Ed Norton, who is nothing short of brilliant and who may or may not be sporting a real boner at one point (he is pretending to have sex with Naomi Watts and, well, he’s going to get one anyway so, as his character concludes, he might as well use it).

The ending is left open to interpretation and initially it did jar a little. In fact, since I really enjoyed everything else this is what prompted me to watch it again and my own personal take is that the central ‘one shot’ epsiode of the film is all real, but both the very beginning and end segments aren’t, they have more to do with a little playfullness on Iñárritu’s part, but also the dreams and desires of Riggan. For me it works well that way at any rate.

I can’t really see anything beating this for best film, actor and director – especially as it’s about the industry and is in itself redemptive, acknowledging its worth, and especially Keaton’s, gives all performers hope, validity and reassurance whether they are currently successful or not. Indeed, I think the best way to approach any artistic or creative endeavour is to simply put yourself into the work, and by that very process you become the thing – if you have sung onstage or recorded music then you are a singer, if you have acted on screen or stage then you are an actor, volume and monetary or critical success aren’t really relevant in terms of validation, if you beat yourself up chasing the latter then what’s the point in doing it in the first place? Enjoy the art of creating, and if fortune smiles your way so much the better, but the pride in actually doing something and having the balls to do it should always be placed paramount above all else. If you love film and/or have spent any time around the vibrant internal organs of a theatre, then you will love Birdman.